As ecological gardeners, we grow to know and love “keystone species'“ of the Plant Kingdom, scientifically found to support the greatest number of Lepidoptera (the caterpillars of moths and butterflies). For the herbaceous plants in Eastern Temperate Forests, the top 3 performers are: Goldenrods (Solidago spp.), Asters (Symphyotrichum spp.), and Perennial sunflowers (Helianthus spp.). Douglas Tallamy is claim to fame for crediting Oaks (Quercus spp.) for being the keystones of the woody world, along with wild cherries (Prunus spp.) and birches (Betula spp.).

Solidago graminifolia in a Waxwing garden

Helianthus occidentalis ssp. dowelianus in a Waxwing garden

Symphotrichum oblongifolium ‘October Skies’ in a Waxwing garden

As defined by Britannica encyclopedia, keystone species have a “disproportionately large effect on the communities in which it occurs. Such species help to maintain local biodiversity with a community either by controlling populations of other species that would otherwise dominate the community or by providing critical resources for a wide range of species”.

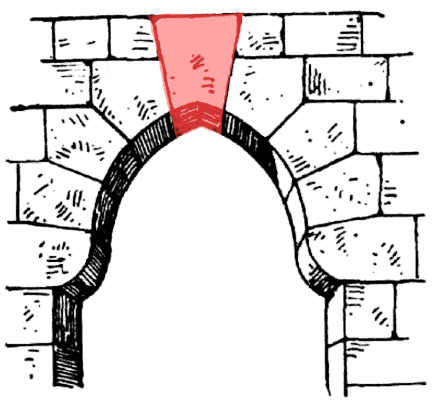

The imagery of this essential stone in a classically crafted arch for bridge construction, coined by American zoologist- Robert T. Paine in 1969, helps to conceptualize the dependency that the majority of the other stones have on this key piece.

Keystone. Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Keystone_%28architecture%29

Likewise, a disproportionately large number of Lepidoptera species are dependent on a select few keystone native plants species. These species are like the red block, pictured above, powerhouses for wildlife, fueling a large percentage of your backyard habitat’s food web.

On a more macro level, within the Animal Kingdom, beavers are deemed the movers and shakers within ecosystems of our region. Bolstering biodiversity by creating wetland ecosystems along waterways, increasing habitat for a large variety of flora and fauna. Without the beaver, more stormwater rushes through landscapes, without having the opportunity to slow down and recharge the water table. The arch collapses.

A pair of young beavers. Image source: https://www.bayjournal.com/columns/chesapeake_born/leave-it-to-beavers-species-ability-to-alter-land-should-be-revisited/article_d587a939-1f8e-58c4-92ea-b74a97538259.html

So, the question begs, as the title of this blog suggests, are humans also keystone species? This is a struggle for some of us to ponder and it may stem from this imagery that has sorely been our egotistical understanding ourselves on planet Earth. Humans as habitat destroyer, mountain mover, land paver, resource extractor, and water polluter.

The misconceived thought that the planet is for us and for us only. Within our ecological gardener community, some of us may not be at peace with our species, stemming from many of our recent collective and destructive choices as a species. We are in fact living in the “Age of the Anthropocene” after all.

“Ego-Eco”. Image source: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Diagram-Ego-Eco-Humankind-is-part-of-the-ecosystem-not-apart-from-or-above-it-This_fig1_330697869

Will we embrace an “eco” paradigm shift, where we humbly see ourselves as one species within a rich tapestry of diversity on Earth? A way of life demonstrated by other human cultures for thousands of years. Will we heal our relationship within our own species, accepting the stories that were left to fully sculpt the character of our species, and to craft new stories of healing and reciprocity?

Note: To dig deeper into the concept of reciprocity, please if you haven’t done so already, do check out “Braiding Sweetgrass” by Robin Kimmerer- life changing for many ecological gardeners. Side story: When I met her at a recent book talk event, I felt so compelled to give her a gift, in exchange for all the rich gifts she shares, in word, in this book. So, I gave her the only thing I had with me, a Waxwing canvas tote bag and left with my signed book all speechless and swoony. Those who know me, I’m not one for being left starstruck <blushes>.

Lancaster city youth watering raised container native mini-meadows to support greening effort on their block.- Spring ‘22

Will we heal from our past destructive action? Will our healing within our own species go so deep that we then give back and fundamentally restore the natural systems that have sustained us so generously?

If so, will we then go as far to say we are a “keystone species” in this new era? A species that is so pivotal to the future of our planet; our intellect so key, so vital in rebuilding biodiversity on planet Earth? Helping broken soils (American’s herbicide lawns!) remember who they once were and to possibly even create intensely genetically rich gardens, backed by compiled entomological research to support Lepidoptera in ways only a human could research and craft? Beautiful demonstration of this recently brought to fruition at the Arboretum at Penn State!). Field trip anyone?

Arboretum at Penn State, Phyto Studio. Image source: https://www.phytostudio.com/psu

Is the survival of the Monarch butterfly highly dependent upon Homo sapiens sapiens? Is the preservation of the memorable song of a wood thrush in the hands of humans? Is the health of waterways and access to clean drinking water pivotal on the action of our species? Is the continuation and necessary bolstering of the biodiversity of our national forests, state forests, public lands dependent upon us? Are we a key stone in this bridge to the future of the planet?

Last question, I promise ;). Is the act of saying “yes” to all of the above “ego” or “eco”? If we move forward with acceptance of this vital role to play as earth citizens with fascinating intellects, empathy to offer, and sweat to outpour, then it can be argued its the most humbling of pursuits.

“Wild Plant Culture” by Jared Rosenbaum.

Jared Rosenbaum, author of recent book release, “Wild Plant Culture: A guide to Restoring Edible and Medicinal Native Plant Communities”, beautifully and poignantly calls humans to be keystone animals that steward and tend diverse wild communities. The greatest quest, he shares, is to “fully integrate the most challenging animal of all- the human being- into our native plant gardens”. We can do so by informing our actions through traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), a cultural practice with the land that has unfortunately lost its way in European colonization.

To culminate this concept of embracing human as “keystone”, let’s take it one step further. Do we also feed ourselves with the native plants that we bolster are backyards with? This lens is very easy to swallow for the lifelong forager or proud permaculturist, but maybe not as easy to embrace for the ecological gardener that came to this practice in deep empathy for wildlife, not their own species. Arguably, it is essential to first build back biodiversity for the other-than-human species; to feed our struggling kin, before feeding oneself, who has historically taken for generations.

Though once we have enriched our human spaces with that initial motivation to rebound wildlife populations, can we then feed ourselves with the same rich fruits, seeds, nuts, and greens? Not to be confused with unsustainably taking from dwindling wildlife populations’ essential food sources; again, they dine first. We have conventional ag, unlike our coevolved wildlife kin that only can eat native plants. Groceries/markets are our transition until we can sustain fully perennial native edible landscapes. Will we respect our species- humans- to the full extent of enriching our cells also with the plants that our wildlife friends and, of course, our indigenous kin once too sustained on?

Mountain mint in a patio pot at Waxwing’s first HQ in Lancaster city.

It turns out that when we consciously choose to steward habitats for wildlife AND also for our sustenance, we immerse ourselves fully as being part of nature, not separate from it. And when that happens, we can then begin to see ourselves as a “keystone species”. Doesn’t that just make you want to jump up and dig some pawpaws and medicinal mountain mint into the earth?

We can “free to birds with one hand”, by choosing to consciously plant species that not only are native and high yielding for wildlife, but also happen to be highly nourishing for humans too! So, if you’ve never eaten a wild perennial plant and are thinking, how on earth would I even start on this adventure? Well, don’t start with mushrooms ;) . I suggest to my customers to begin with “low hanging fruit”, a wild food that tastes good, freshly picked off the plant, that doesn’t need preparation.

Backyard harvested serviceberries at Waxwing’s first HQ in Lancaster city.

Serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.)- pick and eat those antioxidants! I promise the tree has more fruit than wildlife can eat, I often pick fruit along with the squirrels and cedar waxwings higher in the branches, we all dine collectively. You are the keystone, plant that tree.

Here’s a cool example for those that love to stack a boat load of functions into their actions… plant AND eat anise-scented goldenrod (Solidago odora). Its a KEYSTONE native herbaceous plant AND a nutritious little topper to your salad. Check those leaves to give the baby Lepidoptera first dibs!

One last example to toast the human quest of healing our understanding, our role, in this building back biodiversity adventure. American plum (Prunus americana), a keystone native plant AND a caloric fruit packed with vitamin A, K, B5, C, and potassium. A shout out to friend and Waxwing contractor, Donna, and her edible native nursery, Fernwey, for making this homemade American plum wine. Raise a glass- be well in this new year keystone kin!

American plum (Prunus americana) wine, made by Donna in a 2022 wine-making workshop at Rising Locust Farm.

Have you embraced the role of being a keystone species? Do you love munchin’ and crunchin’ on native plants? Give the post some “Love”, share with a friend, and/or comment below!